Evolution of Commercial Open Source Licensing #

TLDR: Commercial software vendors’ licensing strategies are rapidly changing — yet again. License changes and their impacts can be overwhelming for engineers, managers, and open-source software (OSS) contributors, so I aim to break them down in this article.

Evolution of open source licensing models

How did we get here? #

OSS vendors need protection from hyperscalers #

This all started around the 2010s, when commercial vendors who initially leveraged open-source licenses for distribution and adoption found their business models under threat from cloud providers, such as hyperscalers like AWS. While they reaped the benefits of being free, i.e., usage spread quickly and widely, the downside was that competitors could freely utilize years of labor and offer competing services, often at a scale that the original open-source companies couldn’t match. This conflict drove the exploration and implementation of alternative licensing strategies, creating a new type of license that is still effectively open source, but with an added clause preventing the use of the software to compete with the vendor. One such license type is the AGPL, which I have extensively discussed in my earlier post here.

While these new licenses drove adoption as good as purely open source licenses, they also allowed vendors to block new entrants in the market. Any new fork of the project would then have to contribute changes back to the open-source project. This model also prevented price gouging — Say if a vendor jacks up prices, or takes a drastic new direction, users or the community could fork the project (i.e., create their independent version), acting like a built-in accountability mechanism.

To summarize, the primary benefits were “frictionless distribution” and the inherent threat of a fork, which arguably kept vendors from abusing the software lock-in.

Cloud infra OSS vendors need more protection from AWS. #

One downside to this was that the need to shield users from strong copyleft licenses, such as AGPL, for infrastructure components led to complex licensing schemes that included permissive licenses for interfaces. AGPL requires you to open-source your code if users interact with it over a network, while cloud infrastructure products, such as logging tools, do not directly interact with the user.

To overcome this, around 2014/2015, vendors began creating and utilizing new, stricter source-available licenses, also referred to as non-compete licenses or source-available licenses. A key example is MongoDB’s Server-Side Public License (SSPL). SSPL goes further, requiring you to open-source your entire service stack if offering the software as a service. SSPL addresses scenarios where businesses provide the functionality of the covered work to third parties as a service.

MongoDB initially transitioned from an open-source license to the Server-Side Public License (SSPL) to prevent cloud provider competition. However, this shift created some distrust of commercial open source — there was quite a strong adverse reaction from many corners of the open source community. Many viewed it as a fundamental step away from the core principles of open source, as it felt like closing off something that was meant to be open.

Around 2019, the concept of a “triple licensing strategy” for commercial open-source firms was articulated. This strategy involves offering a commercial license, a non-compete license for adoption, and a strong copyleft license for open source goodwill. Now in 2025, Triple-licensing is emerging as a potential strategy, particularly for mature vendors that have already experienced forks (e.g., Redis, Elasticsearch).

Triple-Licensing Strategy #

The basic idea is to offer the software under three distinct licenses simultaneously. Presented as a potential solution to the problems faced by infrastructure component vendors, this strategy involves offering three licenses:

- First, you’d have a plain, strong copyleft license, such as the AGPL. This is for the open-source purists, the community members who value that guaranteed freedom and sharing. To maintain the “mantle and goodwill of open source” and simplify licensing complexity compared to the older mixed-license approach. It should be noted, however, that nobody collaborates around strongly copyleft-licensed code unless they are a die-hard free software supporter. It’s essential to recognize that the strong copyleft license in triple licensing is primarily intended for “open source goodwill, nothing more, nothing less,” and does not promote collaboration or drive adoption.

- Second, you’d have something that’s almost like SSPL, designed for adoption, but crucially prevents the direct cloud competition we discussed. This license “replaces the original permissive-shields-for-a-copyleft-core strategy” for driving adoption. We can call the ‘anti-AWS’ license!

- Finally, a pay-for commercial license for traditional paying customers. This is the most restrictive option for users and lacks the “frictionless distribution” benefit of open licenses; however, this license generates revenue.

Most recently, Redis transitioned from an open-source license to SSPL 1.0 (non-open source) in March 2024—one big stir. However, just over a year later, in April 2025, they reversed course and re-licensed under AGPL-1.0 as part of a triple-licensing strategy.

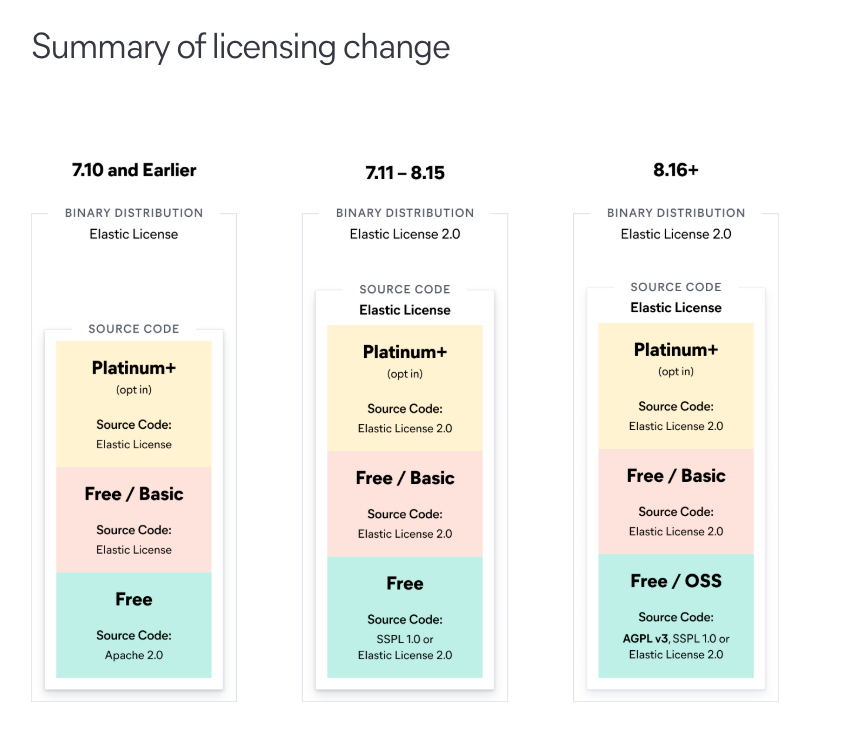

Elasticsearch did something similar, adding AGPL back into their mix after initially moving away from pure open-source. The ‘free’ tier in the screenshot below, from the Elasticsearch license page, clearly illustrates this change across different versions.

Elasticseach ‘free’ version moved from Apache to SSPL and then from SSPL to AGPL+SSPL over the years

Concerns with a triple licensing model #

What can go wrong with this triple license model? Personally. I have a few concerns.

Firstly, vendors can tighten control by removing the free-to-use option entirely after establishing adoption with source-available licenses. This is seen as a potential future “payday” for vendors and a likely cause for users to “wake up.” If vendors regularly drop their source-available licenses, it may force new commercial open-source startups to adopt permissive open-source licenses from the outset. This would make “trademarks, quality, and speed” their primary competitive differentiators, which the author views as “probably a good thing.”

Secondly, while triple-licensing simplifies licensing for infrastructure component vendors and provides a veneer of open-source goodwill, it does not drive adoption or foster collaboration, which is detrimental to the project and the community.

This article was originally published on Medium as part of the BoFOSS publication.