AWS Just Proved It’s the Internet’s Biggest Single Point of Failure #

tl;dr: AWS broke everything with a typo. Supabase ran out of servers for 10 days after raising millions. The cloud is held together with duct tape and hope.

A single DNS typo—one character—pwned 2,500+ companies simultaneously. Netflix. Reddit. Coinbase. Disney+. PlayStation. The digital economy’s entire Jenga tower collapsed because someone fat-fingered a config file.

The 130-Minute Catastrophe #

The Problem: DynamoDB’s DNS broke. The Real Problem: Every Lambda function in existence depended on it. The Actual Problem: SQS queues backed up like a Black Friday checkout line.

The Failure Chain:

- DNS misconfiguration in US-EAST-1 broke DynamoDB endpoint resolution

- Lambda functions couldn’t find DynamoDB → started timing out

- SQS queues fill up because Lambdas can’t process messages

- Dead Letter Queues (DLQs) overflow, creating secondary backlog

- CloudWatch alarms trigger everywhere, PagerDuty melts down

- Auto-scaling groups spin up more instances to handle the “load” (spoiler: doesn’t help)

Here’s the thing nobody tells you about serverless: It’s only as reliable as its stateful dependencies. Lambda scales infinitely (in theory). DynamoDB is your bottleneck. When DynamoDB’s DNS dies, your entire serverless architecture becomes a very expensive retry machine.

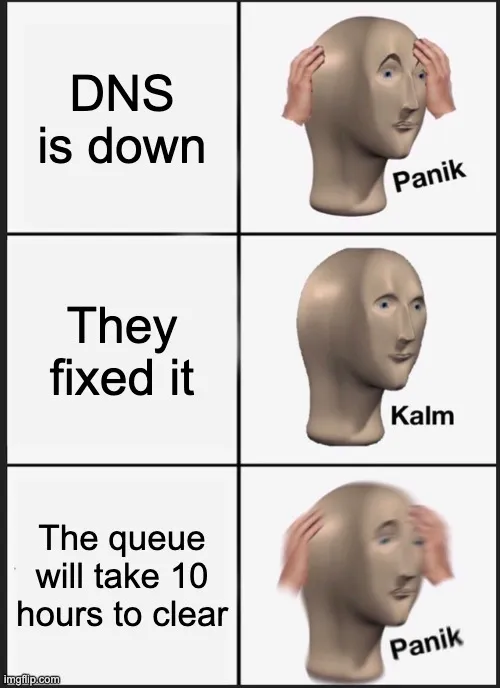

Fixed in 2 hours. Recovered in 12. Why? Because fixing the typo was easy. Clearing millions of backed-up Lambda jobs? That’s like trying to unclog the entire internet with a plunger. AWS engineers: Fixed it in 130 minutes! The Queue: Hold my 47 million pending tasks

Digital Monoculture = Digital Extinction Event #

Here’s the based take: We’ve built a system where one region going down creates a cascading failure across the entire planet. That’s not resilience. That’s a single point of failure with extra steps.

---

---

Supabase: The 10-Day Cope Session #

Right after Supabase announced their massive Series E funding round—like, immediately after—their EU-2 region just… stopped working.

For 10 days. The excuse? “We ran out of nano and micro instances, and that’s mostly AWS’s fault.”

Here’s what happened: Supabase relies on AWS EC2 for their hosted PostgreSQL instances. They use t4g.nano and t4g.micro instances (ARM-based, cheap, efficient) for dev branches and smaller projects.

The problem:

- AWS has capacity pools per instance type per availability zone

- Popular instance types can get exhausted during high-demand periods

- There’s no SLA guaranteeing availability of any specific instance type

- Supabase’s entire branch-creation workflow depended on these instances being available

Meanwhile the customers:

- Can’t restore backups ❌

- Can’t restart instances ❌

- Can’t create branches ❌

- Can’t do literally any dev work ❌

Even paying customers were bricked. You could stare at your production database, but you couldn’t touch it. It’s like having a Ferrari with no gas stations within 1,000 miles.

Blaming AWS didn’t land well when you’re a managed platform company and your entire value prop is “we handle the infra”. Plus you just raised millions of dollars and paying customers couldn’t work for a week and a half!

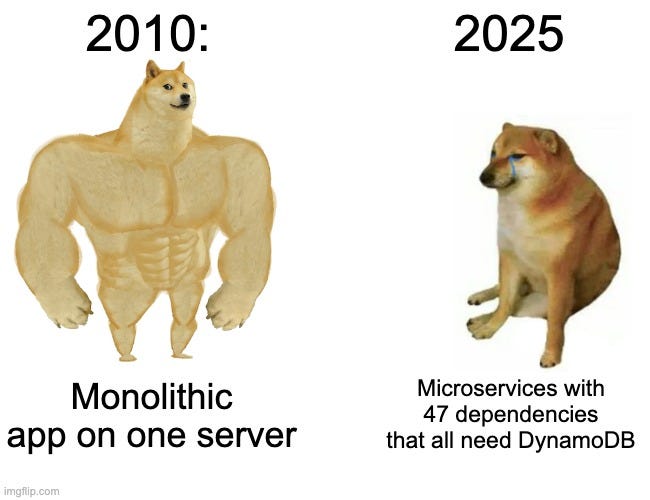

A smarter move would’ve been multi-region architecture from day one. Instead we see companies running with monoculture dependency, single vendor lock-in, zero redundancy.

The Bottom Line #

Managed services != managed risk — Well most of the time managed services manage risk, until your vendor runs out of servers

DNS is still the internet’s Achilles heel — One typo can glass an entire region.

Your SLA is only as good as your weakest dependency — And that’s probably AWS US-EAST-1

Observability > Optimization — You can’t fix what you can’t see

The pendulum is swinging. Hard. Self-hosted infrastructure with actual resilience engineering is starting to look less like paranoia and more like basic hygiene. When a DNS typo can detonate half the internet, and a capacity shortage can paralyze production for 10 days, maybe—just maybe—we need to stop pretending “the cloud” is a magical solution and start treating it like what it is: Someone else’s computer. And it can brick at any moment.

This article was originally published on Substack as part of the BoFOSS publication.